Putting the perfect sundae together - daydreaming of sandcastles and assessment

- eliciabullock81

- Dec 7, 2025

- 4 min read

Over the last few months I have been spending some time exploring assessment theory. During this time my understanding of assessment has shifted in meaningful ways. Firstly, I realized that many of concepts around designing engaging tasks, supporting equity, and prioritizing student growth were already present in my teaching. However, this learning journey has given me a deeper and more theoretically grounded sense of what it means to design intentional, authentic, and equitable assessment. My Sandcastle Assessment represents that synthesis.

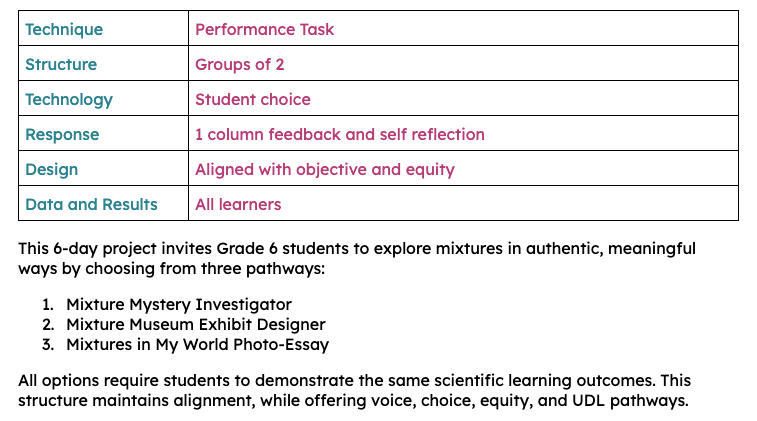

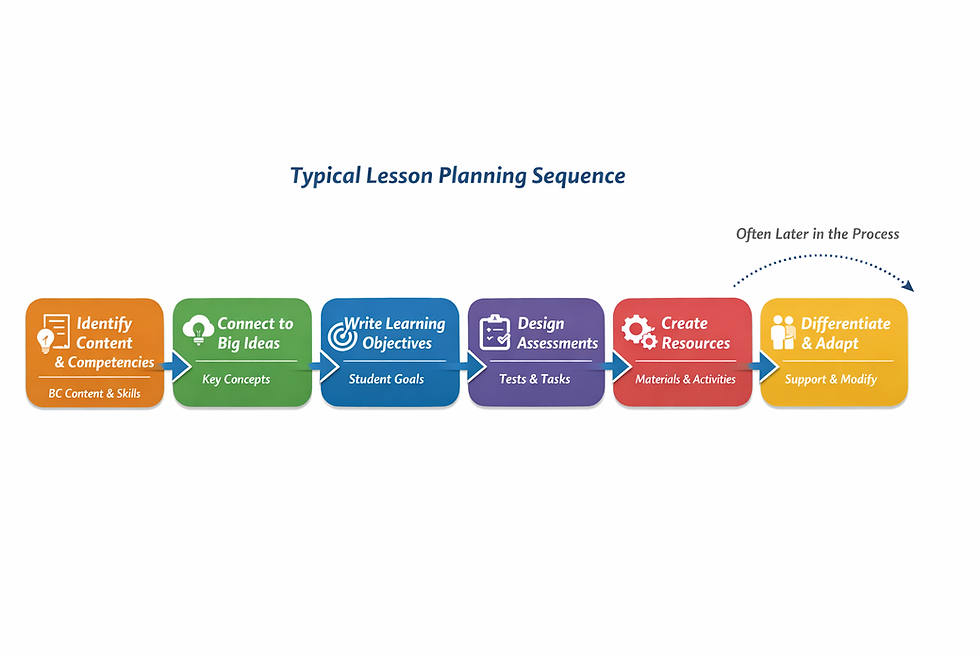

This assessment fits into my broader practice as part of an upcoming Grade 6 science unit on Mixtures. Previously, this unit relied on hands-on activities, worksheets, station work and a rounded out with a summative test. I found that while a large portion of the students did fine with the assessment, engagement in some of the more challenging station activities was low despite them being real science tasks. Now, drawing on backward design principles (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005), I began not with activities, but with the core competencies I want students to develop: observing, analyzing, evaluating evidence, applying scientific reasoning, and communicating clearly. These competencies shaped every decision that followed.

While backward design has long guided my planning, this course shifted how I understand the quality and purpose of assessment within that framework. I had been aligning outcomes, tasks, and rubrics for years. What has changed for me is not the foundation of backward design, but the way I now think about what counts as meaningful evidence of learning and how to design assessments that are both authentic and equitable.

Readings from Shepard (2000), Montenegro and Jankowski (2017), and others helped me recognize that alignment alone is not enough. Tasks must invite students to engage deeply, draw on their lived experiences, and demonstrate understanding through purposeful, real-world inquiry. Although I always aimed to make learning engaging and interactive, I now see more clearly how assessments can intentionally center student voice, process, and equitable access. This new assessment is a performance task that aims to have students become the scientist in their own life by selecting mixtures that they want to explore.

Starting from competencies, I designed a task where students think and act like scientists. Rather than recalling definitions of mixtures, they investigate one, justify their conclusions with evidence, and communicate their findings clearly. This reflects Shepard’s (2000) argument that assessment should support a culture of learning, where students engage in sense-making, not compliance.

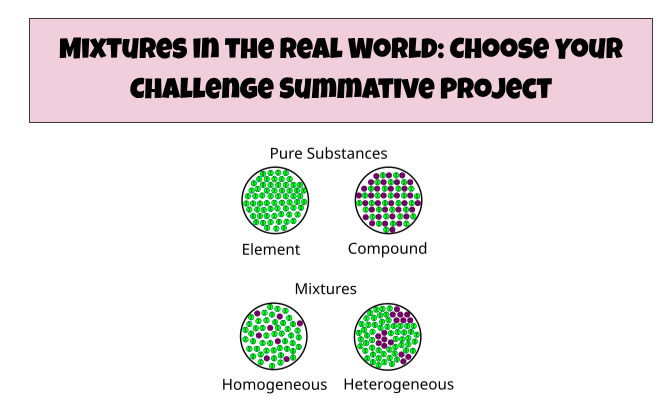

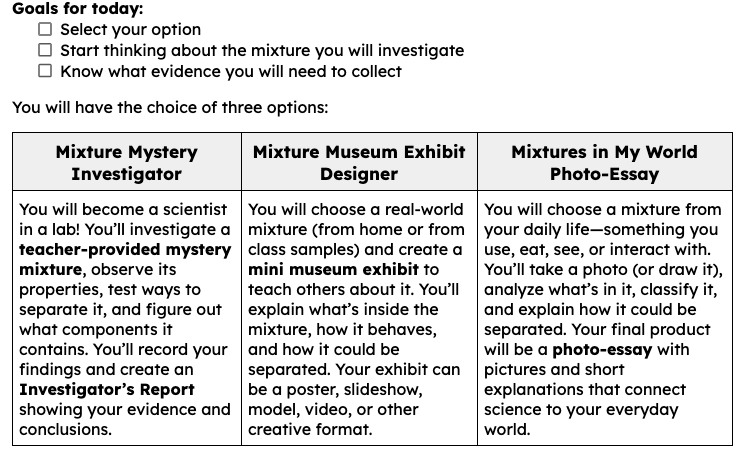

The project provides three pathways (Mixture Mystery Investigator, Museum Exhibit, or Photo-Essay) but all students must demonstrate the same criteria, assessed with a single, transparent, criterion-referenced rubric. This maintains fairness while supporting variability and learner agency.

If you were a Grade 6 student, which option would you choose?

🔍 Investigator

🏛 Museum Exhibit

📸 Photo-Essay

Teacher check-ins act as formative feedback loops, allowing me to surface misconceptions early. Because the work relies heavily on student-generated evidence—observations, sketches, notes, photos, students cannot bypass the learning process. This produces meaningful data, both for teaching and for reflection, supporting Shepard’s (2000) framing of evidence-informed practice.

Montenegro and Jankowski (2017) emphasize that equitable assessment requires attention to identity, context, and access. These principles guided my choices in allowing voice and choice in the tasks students would complete. It also helped me structure a booklet that had built in scaffolds to encourage scientific thinking and language, as well as support student with various needs. Students were provided the opportunity to draw, write and model their thinking reducing linguistic and cognitive barriers. Finally, I chose to provide a large amount of in class time with no expectations of completion at home. I hoped to minimize inequities related to time and support outside of school. Each element was designed to ensure that students are assessed on what they know and can do, not on what they have access to.

My assessment exploration also challenged me to reconsider the role of technology in assessment. Selwyn (2016) warns that technology often reinforces surveillance or efficiency rather than learning. In contrast, this project leverages technology to document learning, not police it.

Students use tools such as digital photos, drawings, and drafted slides to capture their scientific process. I use these artifacts to guide feedback. Technology becomes a record of thinking, not a mechanism of control, supporting equitable and student-centered assessment.

This Mixtures assessment reflects the synthesis of my evolving assessment identity. Through my learning, I now have a more clear path to designing assessment see assessment as something that is not only intentional, with clear links to the learning outcome but the science competencies as well. Building upon my Backward design principles I have embedded in principles of authenticity, equity and manageability. Most importantly, it reflects my growing commitment to building assessments that promote curiosity, confidence, and scientific thinking and that honour the diverse learners in my classroom.

References:

Hawker Brownlow Education. (2013, July 17). What is Understanding by Design? Author Jay McTighe explains. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d8F1SnWaIfE

Kohn, A. (2011). The case against grades opens in new window. Alfie Kohn. https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/case-grades/

Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N. A. (2017). Equity and assessment: Moving towards culturally responsive assessment opens in new window. (Occasional Paper No. 29). University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA).

Selwyn, N. (2011). Education and technology: Key issues and debates. Continuum International Publishing.

Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4–14.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). ASCD.

Comments